Kelly

D. Edmiston Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City

Marcus X. Thomas Georgia State University

Introduction Objectives of the Study

This study was prepared to ascertain the magnitude of the commercial music industry’s economic impact on the State of Georgia. The report was funded by a grant from the Film, Video, and Music Office of the Georgia Department of Industry, Trade, and Tourism.

During the last decade, Georgia has seen tremendous growth in enter-tainment-related businesses and events. During the 1990s several key events helped to position Atlanta as an international center for art, tourism, and commerce, including events such as the 1994 and 1999 Super Bowls, several major league baseball playoffs and World Series and the 1996 Olympic Games. During the same period, Atlanta also witnessed a substantial growth in the number of music recording establishments, record labels, and other professional services connected with the commercial music industry. Companies such as LaFace Records, So So Def Recordings, Hitco Music Publishing, Dallas Austin Recording Projects, Silent Partner Productions, and Sony Music ATV established home offices in Atlanta during the 1990s.

The report demonstrates the commercial music industry’s significance to the state and local economy and explains how the industry has affected the growth of Georgia’s music culture. We explore what we perceive to be the strengths and weaknesses of Georgia’s music industry and identify opportunities for expansion of the indigenous industry and attraction to foreign industry to establish offices in Atlanta.

Outline of the Study

We first highlight historical and recent achievements by Georgians and the local music scene. There is a proud lineage of artists and businesses that have lived or operated in Georgia, and several recent events have catapulted Atlanta into the stratosphere of musically and culturally elite cities. The presence of several major record labels, many recording artists, and entertainment producers has created a strong infrastructure to support the local commercial music industry. Using Standard Industrial Classification codes (SIC), we then ascertain the current size of Georgia’s commercial music industry. We report the size of the industry in terms of number of commercial music establishments, number of jobs created, payroll, gross receipts, and growth since 1990. The methodology section explains the data collection process and sources and gives our rationale for how we chose classifications to include in the study. Based on these findings we report the estimated impact the commercial music industry has on Georgia’s economy in terms of output, employment, income, and tax revenues. We find the total net annual economic impact of the music industry in the State of Georgia to be $989.5 million, with approximately $1.9 billion in gross sales, 8,943 jobs created, and $94.7 million in tax revenues generated.

Highlights of Atlanta’s Commercial Music Industry

The state of Georgia has a long and celebrated history of commercial music production and culture. Georgia has a rich lineage of rhythm & blues, country, rock n’ roll, and rap artists that have forged an undeniable impression on the national music psyche. Through the years, Georgia has been the birthplace and home to many icons of the music industry including Ray Charles, Johnny Mercer, Otis Redding, Ray Stevens, James Brown, Gladys Knight, Ronnie Milsap, Lena Horne, Curtis Mayfield, Isaac Hayes, Trisha Yearwood, Alan Jackson, Chet Atkins, and Travis Tritt, to name a few.1

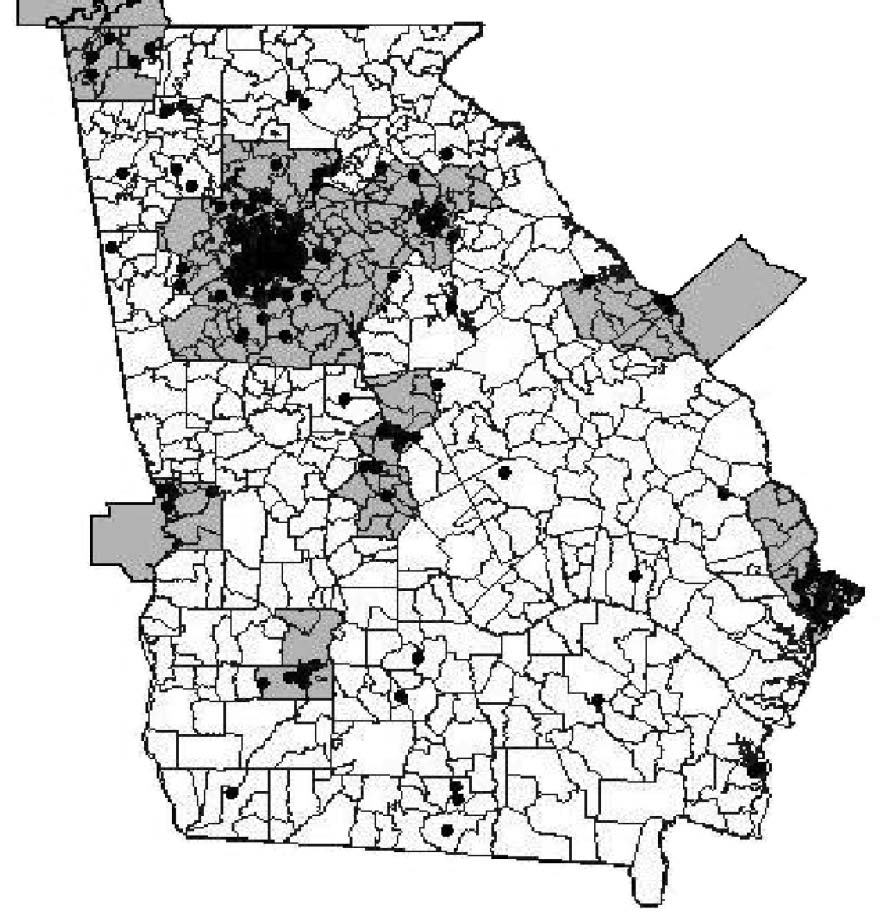

In addition to a formidable who’s who list of rock and rap stars, Georgia also maintains a substantial support industry for the production of commercial music. The majority of this industry is focused in and around the metropolitan area of Atlanta. There are more than 300 recording facilities that produce commercial music and broadcast elements located in Atlanta (Figure 1).

Georgia has several premier venues for showcasing and performing live music, major prerecorded music distributors, a few commercial music education programs, and a plethora of professional services such as music publishing, entertainment lawyers, artist managers, and musical equipment manufacturing, leasing, and repair.

Because Georgia is home to so many producers of commercial music, the city of Atlanta harbors regional offices of the nation’s two major performing rights societies, The American Society of Authors, Composers, and Publishers (ASCAP) and Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI). The city also serves as home to the Atlanta Chapter of the National Academy of the Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS).2

Figure 1. Spatial distribution of Georgia recording

The Regional Significance of Georgia’s Commercial Music Industry

Atlanta serves as the southeastern hub for the commercial music industry. The city is very accessible due to its geographic location, major ground transportation arteries, and Hartsfield International Airport. The five major prerecorded music distributors in the country service the entire southeast region from their Atlanta branches.3 At least one of the major distributors defines the southeast as a nine-state region comprised of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Kentucky, and Louisiana.4 Priorities for determining which products will be sold throughout the region (with exceptions for indigenous music in Florida, Tennessee, and Louisiana) are based in part on sales trends and music consumers’ tastes in Atlanta.

Atlanta dominates regional radio, setting the agenda for what music is played, and consequently consumed, throughout the region. Atlanta’s radio market ranks 11th nationally with an estimated population of 3,617,400 listeners. Of this total, 1,027,700 are African-American.5At 28.4 percent of the city’s listening population, Atlanta’s urban radio scene is one of the strongest in the nation. Atlanta ranks fourth behind New York City, Chicago, and Washington D.C. in the number of African-Americans in the total listening population. Radio programmers throughout the region review play lists of Atlanta broadcast stations to determine which songs should be added to their own rotations.

Due to Atlanta’s importance to regional distribution and radio exposure, most recording artists include Atlanta as a major tour stop and many entertainment-related businesses have made Atlanta their home.

Major Talent

Georgia is home to an astonishingly diverse and talented bevy of recording stars. From the high-profile club district Buckhead to Midtown, Decatur and Stone Mountain major recording artists from genres as diverse as rap, rock, rhythm and blues, jazz, and pop can be found working in coffee houses, clubs, theatres, and studios.

Grammy Award-winning producer and record mogul Jermaine Dupri is an Atlanta native. Dupri is responsible for writing and producing hit records for acts including Mariah Carey, Monica, Usher, TLC, Aretha Franklin, Alicia Keys, Da Brat, and Jagged Edge. Dupri started his music industry career at the age of twelve as a backup dancer for the then rap group Whodini and at the age of nineteen, Sony Music gave him three million dollars to start his own record label, So So Def Recordings.6

Seven-time Grammy nominee India Arie calls Georgia’s Stone Mountain home. Arie, a Motown recording artist, developed a strong fan base in and around Atlanta by appearing regularly at clubs and performing her unique brand of mellow acoustic soul. She worked with local record label/ management company Groovement/Earthseed to create awareness of her music. After touring with the all-female musical show Lilith Fair, she was discovered and signed to a major recording contract.7

Multi-platinum8 recording artist R.E.M has been based in Athens, Georgia since the 1980s and continues to be a driving force behind the college town’s bustling live music scene. The local scene provides a substantial fan base and is a haven for alternative pop/rock bands looking to develop live presentations of their works.

Another Georgia-based group familiar with Grammy Awards and multi-platinum album sales is the hip hop duo Outkast. The duo has created a signature blend of hip hop and soul that has heavily influenced many other rap artists and spurred a subcategory of rap music coined “Dirty South” rap. The Arista Records recording duo also operates a record label and recording facility called Stankonia.

Other major recording artists and producers who make Georgia their home include: Elton John, Peabo Bryson, members of the group TLC, Usher Raymond, 112, the B-52’s, Dallas Austin, Jagged Edge, Montel Jordan, Kelly Price, Monica Arnold, Daryl Simmons, L.A. Reid, Lil’ Bow Wow, Too Short, Babbie Mason, Luther Barnes, Indigo Girls, Shawn Mullins, John Mayer, Arrested Development, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, and Ludacris.

Major Record Labels

In 1989, then Arista Records president Clive Davis signed a joint-venture agreement with Antonio “L.A.” Reid and Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds to form LaFace Records. Immediately, LaFace went to work creating a signature sound that characterized urban music throughout the 1990s. The label was responsible for producing and promoting the artistic talents of Toni Braxton, TLC, Usher, Outkast, Goodie Mob, Az Yet, Shanice Wilson, Tony Rich, Sam Salter, Donell Jones, and Pink. LaFace was also instrumental in mentoring and highlighting the production skills of music producers including Jermaine Dupri, Dallas Austin, Organized Noise, the Dungeon Family, Shekspere, and Red Zone Entertainment. The label also helped to foster several smaller labels such as Bystorm Entertainment and Ghetto-Vision. Reid, along with a handful of other record executives, is largely responsible for placing Atlanta at the forefront of the national urban music scene.

During its stay in Georgia, LaFace Records was a driving force behind the explosion of entertainment-related businesses that located to the state, and in particular, the City of Atlanta. Upon LaFace’s arrival, ancillary businesses such as photographers, recording studios, production companies, music publishers, artist managers, tour support companies, event planners, promoters, live venues, entertainment attorneys, and accountants flourished. The success of the label attracted many aspiring talents who wanted major label access without the expense and competition associated with New York and Los Angeles. Although LaFace Records sold its interests to its parent company in early 2000 and left Georgia for New York, it left behind a very capable infrastructure now in need of a major outlet.

Jermaine Dupri’s So So Def Recordings recently celebrated its tenth anniversary. In one decade the label has launched the careers of Kris Kross, Da Brat, Jagged Edge, Lil’ Bow Wow, Xscape, and Fundisha. The success of Dupri’s label, powered by his savvy marketing techniques and ability to identify and deliver what the public wants, has kept the dream of having a major record label in Georgia alive in the wake of LaFace’s departure.

Other successful labels that have operated from Georgia include Def Jam South, Dallas Austin’s Freeworld Entertainment, and Melisma Records. In February, 2002, a privately held German company, International Development Fund, was to provide 11 million dollars to Anthony “Cheapo” Kirkland to form Kirkland Media, LLC.9 Kirkand’s plans are to open the largest recording studio in the southeast, a record label, management company, and distribution company. The reported deal makes Kirkland Media, LLC the third largest record label in Georgia behind So So Def and Def Jam South. Several large independent labels have also operated from Georgia including Capricorn Records (now Velocette Records), Ichiban Records, and Evander Holyfields’ Real Deal Records.

Recording Studios and Record Distribution

There are over 300 recording facilities to support the artists and labels that record in Georgia. Many of these are smaller production studios and have reasonable rates that an upstart independent artist can afford. There are also several nationally-renowned, first class studios that regularly record projects for major labels. Some of these facilities include Doppler Studios, Tree Sound Studios, Crawford Communications, DARP Studios, Silent Sound Studios, Southern Tracks, and Southern Living At Its Finest Studios. Several Georgia studios have been awarded Grammys, American Music Awards, Emmys, and Oscars for their contributions to music and film recordings. As shown in Figure 1, Georgia’s recording studios are concentrated largely in and around the Atlanta metropolitan area.

Although it varies from year to year, major labels represented by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) account for 80 to 90 percent of music releases sold in the United States.10 As of the writing of this paper, there are five distributors that handle all of the major record labels: Sony, BMG, Universal, EMI, and WEA. The distributors are largely responsible for marketing and promoting records at the retail level and assisting the record labels with radio and street level promotion. Each of the five major distributors operates a branch office in Atlanta that is typically responsible for territories throughout the southeast. The branch offices are a direct link between their representative labels, which are usually in New York or Los Angeles, and consumers throughout the region. The branch distributors expose consumers in their regions to new records and artists by coordinating advertising campaigns, promotional appearances, and live shows.11

Venues and Events

Georgia has several premier venues for showcasing live talent, all of which are located in Atlanta. From the historically significant Fox Theater to the newest clubs along Peachtree Road, Atlanta presents artists at a variety of performance locations. Venues large enough to host major artists such as Whitney Houston or Michael Jackson are limited to Atlanta’s Philips Arena or Turner Field. However, there are many venues suitable for concerts by mid-level and new artists including the brand new 13,000 seat Gwinnett Center, The Tabernacle (formerly House of Blues), The Fox Theatre, the Atlanta Civic Center, Hi Fi Buys Amphitheater, Chastain Park, Centennial Olympic Park, and the Roxy Theater. Atlanta also features dozens of clubs and martini bars where new underground artists are spotlighted such as the Velvet Room, Apache Café, World Bar, the Show Bar, the Cotton Club, 1150, Red Light Café, Smith’s Olde Bar, Eddie’s Attic, Masquerade, and Celebrity Rock Café.

Several major concert and conference events are held annually in Atlanta. Perhaps the most noted is the Music Midtown concert festival held each spring. Music Midtown hosts more than 300,000 concert-goers and 120 performing acts including both signed and unsigned bands during the three-day event.12 Other major concert festivals in Atlanta include the Atlanta Jazz Festival, the Sweet Auburn Festival, and the Montreaux Jazz Festival. The Atlantis Music Conference is a combination of concerts and educational conferences held each summer. During the three-day conference, registrants attend informative panel discussions and workshops held by industry professionals from around the world. Record executives and conference attendees (attendance reached an estimated 2,000 people summer 2002)13 also saw more than 200 artists perform in more than one dozen area nightclubs. Atlantis features performances by artists representing all genres of music including rock, rap, pop, rhythm and blues, Americana, and Gospel.

Commercial Music Education

The Atlanta Chapter of the Recording Academy is the eighth largest chapter in the country with a current membership of 730. The chapter sponsors several educational events annually, including Grammy in the Schools, which brings 500-800 high school students to meet with industry professionals for a day-long conference that explores career and educational options in the record industry.

Those who are interested in a more formal education in the commercial music industry may choose to attend one of several area colleges and universities that offer degree programs or courses in music business and sound recording. Georgia State University’s School of Music has one of the nation’s longest standing commercial music programs. Established in the 1970s, the Music Technology and Management program offers students a choice of either a Bachelor of Science in Music Management or a Bachelor of Music in Sound Recording. The program educates future commercial music professionals in the areas of marketing, promotion, copyright, publishing, artist management, MIDI production, sound recording, and editing.14 Another Georgia school that currently offers courses in commercial music business is the Music Business Institute of Atlanta.

Economic Impact of Georgia’s Music Industry

This section of the report provides information on the size of the music industry in Georgia (its direct economic impact) and presents results from the input-output analysis. It describes the music industry as we have defined it for this study and it presents results from the economic impact analysis. A description of data sources and methodology is presented in the appendix of this report.

The Music Industry Defined

We identified relevant industries by Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code (1987 revision).15 These industries include not only commercial music production, but also manufacturing enterprises, wholesalers and retailers, repair shops, and schools that serve a music-related clientele. Only the subcategories (6-digit SIC) that are specifically related to the music industry were considered. For example, we included only three of the 100 industries aggregated into SIC code 7389, Business Services, NEC (not elsewhere classified). Excluded from this list are retail establishments that sell prerecorded music, although we do include manufacturers and wholesalers of prerecorded music.

Economic Impact of the Commercial Music Production Industry

The music industry in the State of Georgia includes some 1,074 establishments, which generate roughly $1.9 billion in gross sales annually (Table 1). Most noteworthy is that Georgia has 309 recording studios (SIC 7389-47), most of which are relatively small, employing between one and nine people and generating less than $1,000,000 in sales every year. By our estimates, the average of these establishments employs 3.86 employees (including the owner-manager) and generates $347,896 in annual sales. In total, recording studios provide employment for an estimated 1,193 Georgians and generate an estimated $107.5 million in sales.

After recording studios, the next largest category in terms of commercial music production is Orchestras and Bands (SIC 7929-01), which employs an estimated 229 people in the state and generates roughly $43.0 million in sales. Establishments providing musicians and music entertainment generate a combined $35.1 million in sales and employ roughly 231 Georgians.

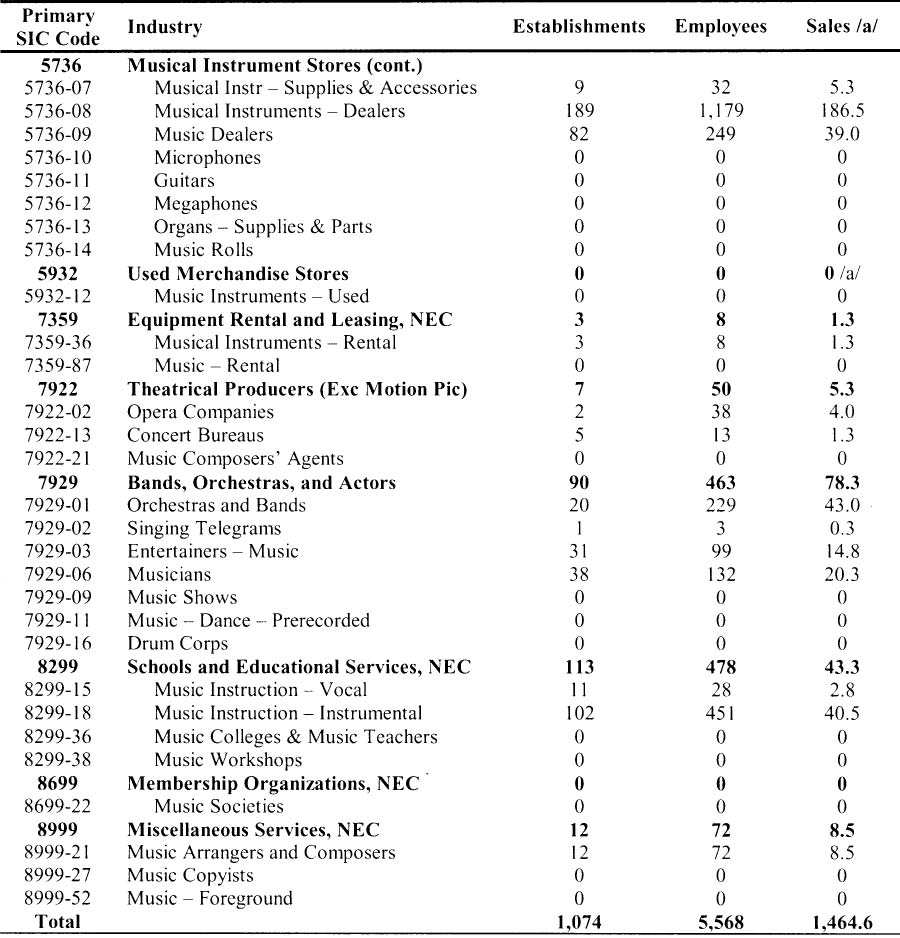

Table 1. Size of the music industry in Georgia.

Table 1 (continued). Size of the music industry in Georgia.

In measuring the economic impact, we do not use sales figures for wholesale and retail industries because they are not reflective of industry “output.” Instead we estimate output based on the number of employees. Note: Columns may not sum to totals due to rounding.

The bulk of sales come from wholesale and retail establishments, for which sales are not a good indicator of “production” because the value of manufactured products is embodied in the sale. For example, a musical instrument manufacturer (SIC 3931) may sell a trumpet to a retailer for $750 (SIC5736), who then sells the same trumpet to a consumer for $1,000.

We want to avoid the kind of output inflation this entails.16The total amount of sales for music-related wholesale and retail establishments in Georgia is over $1 billion.

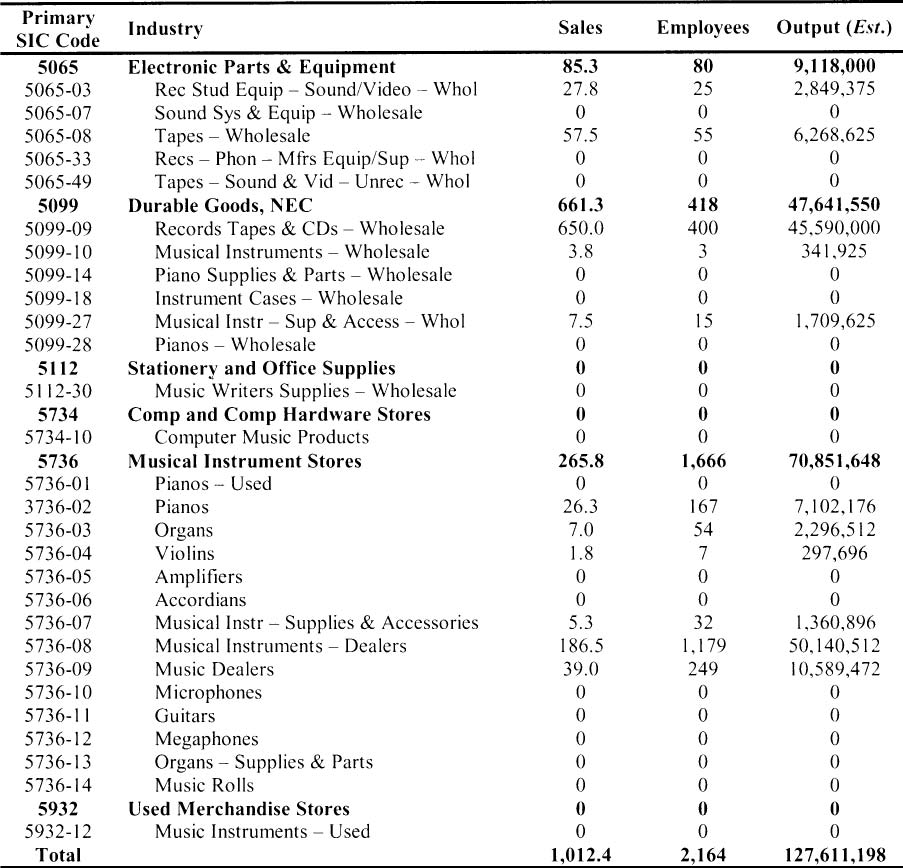

To estimate production, or output, for music-related wholesale and retail establishments we look at the number of employees. Based on aggregate data from the trade industry, wholesale establishments create $113,975 for every employee, on average, while retail establishments generate $42,528 in output per employee. Estimates of output for wholesale and retail industries are provided in Table 2. We estimate that $1,012.4 million in sales generates $127.6 million in output, or that every dollar in sales yields $0.126 in output. Total output for the music industry in Georgia is $580.9 million, and is summarized in Table 3.

Table 2. Estimates of industry output: music wholesale and retail establishments.

We do not use sales figures for wholesales and retail industries because they are not reflective of industry “output.” Instead we estimate output based on the number of employees. Note: Columns may not sum to totals due to rounding.

Table 3. Direct impact of Georgia’s music industry. Note: Columns may not sum to totals due to rounding.

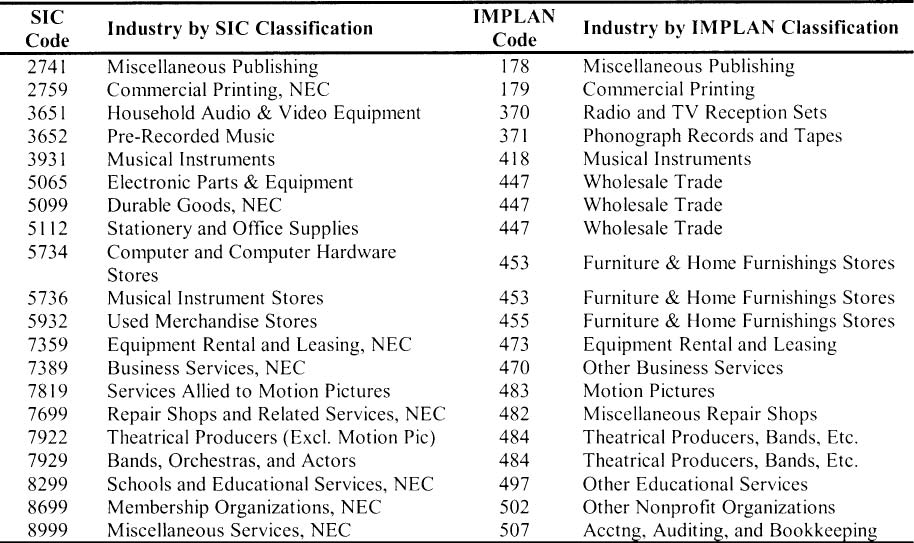

In addition to the direct effect of the music industry in Georgia, there are considerable indirect and induced economic effects. We calculate these secondary effects by using multipliers, as described in the appendix, which are provided by the computer input-output program IMPLAN. Before doing this, we must convert 4-digit SIC sectors into 3-digit IMPLAN sectors. The SIC sectors and IMPLAN sectors correspond very well, as shown in Table 4.

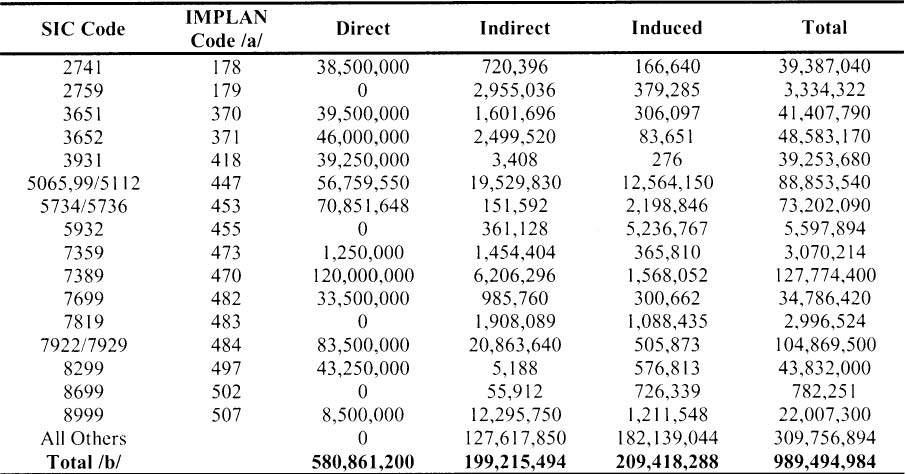

In total, the $580.9 million in direct economic activity generates an additional $199.2 million in indirect expenditure and an additional $209.4 million in induced expenditure (Table 5). Thus, the grand total net economic impact of the music industry in the state is $989,494,984. The implicit output multiplier is approximately 1.70, which means that every $1 of output by the music production industry has a $1.70 impact on the Georgia economy.

Table 4. SIC to IMPLAN Bridge.

Source: Authors; IMPLAN Professional V2.0 Data Guide. (1999).

Table 5. Output Impact.

Note that only the direct numbers refer specifically to the music-related subcategories within the SIC codes listed. The indirect and induced effects reflect impacts on entire SIC categories, which are much broader. Moreover, IMPLAN categories often contain multiple SIC categories. /b/ Rows and Columns may not sum to totals due to rounding.

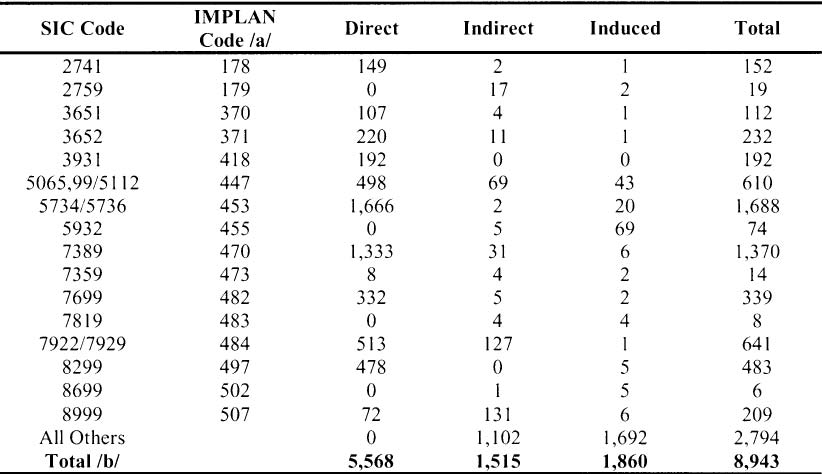

To estimate the employment generated by the music industry (direct, indirect, and induced), we ran the impact analysis again using the employment numbers we estimated from the ReferenceUSA data (as shown in Table 3). By these estimates, which are reported in Table 6, the direct employment of 5,568 people in the music industry generates an additional 1,515 jobs via indirect expenditure and an additional 1,860 jobs through induced expenditure. The total net employment impact of Georgia’s music industry is estimated to be 8,943.

Table 6. Employment Impact.

Note that only the direct numbers refer specifically to the music-related subcategories within the SIC codes listed. The indirect and induced effects reflect impacts on entire SIC categories, which are much broader. Moreover, IMPLAN categories often contain multiple SIC categories. /b/ Rows and Columns may not sum to totals due to rounding.

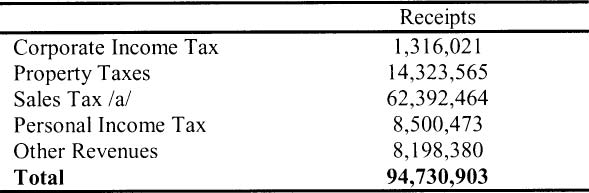

As a final effort we estimate the state and local tax impact of Georgia’s music industry using what is known as a social accounting matrix (SAM). This matrix is similar to the input-output matrix outlined in the Appendix (in fact the input-output matrix serves as part of the SAM), but accounts for inter-institutional transfers like tax payments, household – household transfers, payments of public assistance, interest payments, and so on. The SAM makes it possible to calculate the share of each dollar of output that is paid out in various types of taxes, fines, and fees. Using these multiplier-like figures, we can calculate state and local tax impacts, which are presented in Table 7. The state and local total tax impact of Georgia’s music industry, including indirect and induced expenditure, is roughly $94.7 million.17

Table 7. Tax Impact: commercial music production industry.

Gross sales figures ($1.9 billion) are used to calculate the sales tax impact.

Conclusion

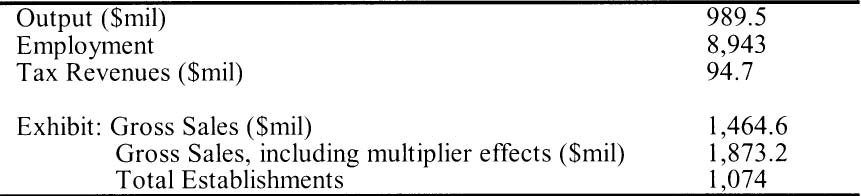

Given its long and celebrated music history, its status as the home of music legends and up-and-coming stars, and its position as the music capital of the Southeast, the State of Georgia, lead by the City of Atlanta, increasingly has become an important magnet for the commercial music industry. Georgia boasts over 300 recording studios, hundreds of artists (some of whom have international fame), premier venues for performing live music, and a substantial commercial music production infrastructure. The music industry generates $989.5 million in output annually, creating roughly 9,000 jobs and generating over $94.7 million in tax revenues (Table 8). In addition to its substantial contribution to the state’s economy, the music industry also makes Georgia a better place to work and live, which has innumerable impacts on the state’s economic development strategy.

Table 8. Net economic impact of Georgia’s music industry.

Appendix: Data and Methodology

Data Collection Process and Sources

Utilizing the ReferenceUSA business directory, a service of the federal government’s infoUSA databases, we were able to collect a wealth of information on each establishment in Georgia that is included in the music industry as we define it, including company name, full address, telephone number, a range for the number of employees, and a range for the amount of sales.18

The ReferenceUSA business directory is a near-exhaustive source for business information in that it covers so many primary sources. U.S.-wide, the database covers more than 5,600 yellow and white page telephone directories; annual reports, 10-Ks and other SEC information; federal, state, and municipal government data; chambers of commerce information; leading business magazines; trade publications; newsletters; major newspapers; industry and specialty directories; and postal service information, including change of address updates.19 The information on each business in the database is telephone-verified every year; firms with greater than 100 employees are telephone-verified at least two times per year. Given the comprehensive coverage of primary sources and telephone-verification, and that the State of Georgia currently does not have a reliable music business directory,20 we feel confident that the ReferenceUSA business directory is the best source for information on music-related establishments in Georgia.

We are able to extract much more reliable data from the ReferenceUSA database than we could from census surveys, the typical resource used for data in impact studies. In doing economic impact studies, one typically is forced to roughly estimate the number of establishments, employment, and receipts from four-digit SIC data. There are a couple of problems with this. First, many establishments and data are not reported in government statistical data because they are sufficiently small that they either are not required to report information or are missed. Second, because the information on establishments, employment, and payroll is derived from a census taken only once every five years, the data is almost always out of date. In our case, because 2002 is a census year and the data have not been released, we would have been forced to utilize the 1997 census, and five years in Georgia’s music industry is a long time. Finally, because the data is reported at the four-digit SIC code level, one would have to make an edu-cated guess as to the proportion of the industry class that is made up of music-related businesses, and then use average values for the industry class to estimate employment and receipts. Even with a comprehensive music directory, one would still be required to estimate employment and receipts using data for the average firm in the relevant industry category (which is likely to include mostly firms that are not at all music-related). With the ReferenceUSA database, we are able to acquire information that is comprehensive, complete, and up-to-date.

Our only problem with the data is that it provided a range for the number of employees and amount of sales, rather than exact figures. For example, employment categories were “1-4,” “5-9,” “10-19,” and so on, while sales were “less than $500,000,” “$500,000 to $1,000,000,” etc. To estimate the amount of sales, we simply took the mid-point of the range. For example, if an industry included three establishments, each with sales less than $500,000 and 1 – 4 employees, our estimate for the industry would be $750,000 in sales and 8 employees (rounding).

Input-Output Analysis

In calculating the economic impact of the music industry in Georgia, we make use of input-output analysis. By including in our impact calculation the indirect and induced effects of production in the music industry, the input-output analysis gives a total (and accurate) picture of the output, employment, and income generated by the music industry in the state.

To illustrate the procedure, consider a world with three industries: A, B, and C. In producing its final output, each industry utilizes some of A, B, and C as an intermediate input. The matrix below shows, for each one dollar of output in each industry, the amount in dollars required of all three industries as an intermediate input (in columns):

| A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

| B |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

| C |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

Thus, industry A requires $0.10 of its own output, $0.20 of industry B output, and $0.40 of industry C output to produce $1.00 of final industry A output. The remaining $0.30 is made up of capital and labor expenses. This means that every $1.00 of demand for industry A’s output generates $1.10 in A output (the $1 expenditure plus the $0.10 of A required as an intermediate input), $0.20 in B output, and $0.40 in C output. The total economic impact of a $1 expenditure on commodity A is thus $1.70, not $1.00. We would say, then, that industry A has a (type I) multiplier of 1.7: every $100 of direct expenditure yields a $170 impact on the economy.

It is clear that any production in industry A generates output, employment, and income in all three industries. The impact does not stop there, however, as the income earned (the remaining $0.30 of expenditure by A spent on labor and capital) will be spent on retail goods and services, housing, etc., which will generate more output, employment, and income, in those industries. In calculating the economic impact of the music industry in Georgia, we consider not only the direct effect (the $1.00 of A), but also the indirect effects (the additional $0.70 of inputs) and the induced effects (from expended income). A type-SAM (social accounting matrix) multiplier represents the sum of these effects, along with an accounting for interinstitutional transfers, and is used in this study to calculate the total economic impact of the music industry in Georgia.

Endnotes

1 Georgia Music Hall of Fame, accessed at http://www.gamusichall.com/.

2 ASCAP and BMI license the public performance of musical compositions on behalf of members/affiliates. They also collect and disburse royalty payments in connection with such performances featured in radio, television, jukeboxes, restaurants, arenas, etc. NARAS is best known for presenting the annual Grammy awards.

3 At the time of this report, the five major distributors are WEA, Sony, BMG, Universal, and EMD. 4 Personal interview with Colin Morrison, Urban Product Development Coordinator, BMG (July, 2002). 5 Arbitron Radio Ratings and Media Research Information, accessed at http://www.arbitron.com. 6 Murray, Sonya, “Instructions On life As A Music Mogul (From One Who Would Know),” Atlanta Constitution, Oct. 30, 2001. 7 Murray, Sonya, “India Rising: Atlanta Singer Leaps From Obscurity To Grammy Glory,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, Feb. 24, 2002.

8 The Recording Industry Association of America is the representative organization of most major recording labels in the United States. It certifies sales of albums in terms of “Gold” or “Platinum” status. Gold status refers to sales of 500,000 units or more up to 1,000,000 at which time platinum status is conferred.

9 Lovel, Jim, “Hip-hop Incorporated,” Atlanta Business Chronicle, Feb.

22-28, 2002. 10 RIAA. Accessed at http://www.riaa.com/. 11 Hall, Charles and Frederick Taylor, Marketing In The Music Industry,

3rd edition, (Boston, Mass.: Pearson Custom Publishing, 2000). 12 Music Midtown. Accessed at http://www.musicmidtown.com/. 13 Atlantis Music. Accessed at http://www.atlantismusic.com/. 14 Ware, Tony, “Get Schooled, URB’s College Special: The Top 10 U.S. Schools and Scenes,” Sept., 2002.

15 The SIC was developed in order to classify establishments by type of economic activity in which they are engaged and for promoting uniformity and comparability in the presentation of statistical data collected by numerous agencies. The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) is an alternative system produced

jointly by Canada, Mexico, and the United States.

16 Theoretically, we could do this for all firms by subtracting the value of intermediate goods, leaving us with a measure of “value-added.” We use output instead to keep in line with standard approaches in impact analysis. Moreover, data considerations would make this kind of exercise nearly impossible. We believe that sales are a reasonable measure of output for non-wholesale, non-retail firms.

17 The federal tax impact is $107.4 million.

18 The database also includes names of company officers with contact information and various other data.

19 See the ReferenceUSA web site’s FAQ page, which can be accessed at http://www.referenceusa.com/au/au.asp.

20 We did acquire the latest version (1999) of the Atlanta Music Directory. However, we were able to identify a larger number of firms in the Atlanta area using ReferenceUSA than were contained in the Atlanta Music Directory, which suggests that many establishments were missed in that publication.

KELLY D. EDMISTON is a Senior Economist in the Community Affairs Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. His primary interests include regional economic growth and development and state and local public finance. His work has been published in Economic Inquiry, the Journal of Regional Science, the National Tax Journal, Public Finance Review, and the American Review of Public Administration, among others. Prior to joining the Federal Reserve, he served as an Assistant Professor of Economics in the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies at Georgia State University. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Tennessee.

MARCUS X. THOMAS is an Assistant Professor and Coordinator of the Music Management program at Georgia State University’s School of Music. He received a Juris Doctor degree from Georgia State University College of Law in 1999 and a Master of Mass Communication from the University of Georgia in 1996. His research interests include Copyright Reform, Music Business Entrepreneurship, and Emerging Recording Trends and Technologies.

Financial support for this project was provided by the Film, Video, and Music Office of the Georgia Department of Industry, Trade, and Tourism. The authors would like to thank David Sjoquist, Greg Torre, Bobby Bailey, and John Haberlen for useful comments and suggestions. George Manev provided valuable research assistance.